Ah, those "rabid and deranged anti-cycling nut-jobs versus the humourless, wannabe-martyr, pro-cycling zealots": this from Globe columnist, Andrew Clark's piece last weekend on the 'debate' around how to make cycling safer, as he characterizes the factions engaged in this 'discussion'. (http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-drive/car-life/prying-the-lid-off-the-cycling-debate/article4386683/). Aside the rather balanced presentation (in opinion pieces, how exceptional is that!), what caught my attention was the glaring absence (in the respective positions, not Mr. Clark's editorial) of middle ground.

What seems to have 'blown the lid off' (pun intended) is the great 'to helmet or not to helmet' quandary -- and only because there's so much competing 'evidence' (both for and against). Mr. Clark cites the main findings from the Ontario Coroner's Office review, somewhat darkly entitled Cycling Death Review -- both consciousness raising efforts at all community levels and ways of making the roads safer with facilitation of shared use (bike lanes, safe passing distances, etc.). But evidently it all comes down to those 'dorky little lids', the battle lines drawn up tighter than a helmet strap on a double chin, each faction quoting research that supports its particular perspective.

Con: Violation of individual choice (no doubt, there's a Charter of Rights challenge lurking somewhere in the wings). Drivers actually targeting cyclists in helmets (Hmm, certainly my focus when I get behind the wheel vs. getting on the wheels). Allowing communities to ignore 'meaningful infrastructure change' by passing restrictive helmet laws. Killing (poor choice of words) ride-sharing programs. And Pro: Helmets are like seat belts -- they don't prevent accidents; but you may just survive one (reducing serious injury by 85%). Good modeling -- how do you expect your kid to wear one if mummy and daddy don't. And so it goes.

Caught up in a good old fashioned gossip session this same weekend, I was reminded of just how compelling -- and distorting and selective -- extreme postures on near anything (or anyone) can be. A delightful, though independent thinking and perhaps just a little opinionated friend was waxing descriptive on the cons (not even a token 'pro' in sight) associated with a mutual acquaintance whom I've always found, well let's just say, benign. (That's a polite way of saying that there are elements with which I struggle -- but I've always seen these as 'quirky' rather than overtly malicious.) Descriptors as controlling, self-absorbed, disrespectful, oblivious, obtuse. . . well, I think you likely get the drift, surfaced as the rant built steam. I was particularly curious about my own subjective response to this (to understate) extreme characterization. I immediately felt compelled to either jump on board, to scan my own opinion repository for 'supportive data'; or to oppose, to rebut, to challenge these attributions that didn't resonate with me to any real extent. Where had that middle ground gone?

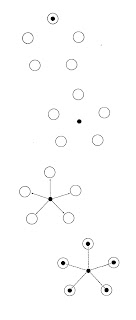

So unsettling was the experience that it spurred a bit of additional self-examination, introspection. As a sort of word-association variant, I made a short list of various folk in my immediate experience and, trying my best not to clutter up the landscape with facts, attached a 'valence' (little +'s or -'s) to each. The egotistical one, the slick one, the self-important one, the generous one, the patient one. . . this was pretty easy -- seeing the world in two dimensions, pro or con, black or white. And beyond this, how simple it was to find evidence to support each of these unitary appraisals. Then came the hard part of the exercise: stretching that characterization to include the offsetting, or more properly balancing elements . . . that complete the picture, acknowledge the complexity of the human state. Suspending the stereotype and restoring the middle ground. Less facile but decidedly more representative.

In mindfulness practice, a sought after state is that of equanimity, a balanced, calm, emphatically non-polarized posture. One that emphasizes the middle ground and typically one that is only available with some measure of intention, of conscious consideration -- no automatic judgments here. The challenge it would seem is to entertain the whole package -- not just those 'juicy' and immediately satisfying epithets that characterize the extremes.

With our cycling 'camps', the goal(s) -- sharing space (in this case, the road), keeping people alive and fit, maybe even doing the planet a favour -- somehow get lost in the stereotyping and adversarial stances, reducing the issue to an aspect that is able to be vilified or celebrated; attributing all manner of 'personality characteristics' to the occupants of one position or the other. In our day to day, how difficult it is to first notice that we're 'sliding to the edge' once again; and secondly, pulling it back with a little injection of equanimity. Put that on your pillow and sit with it!